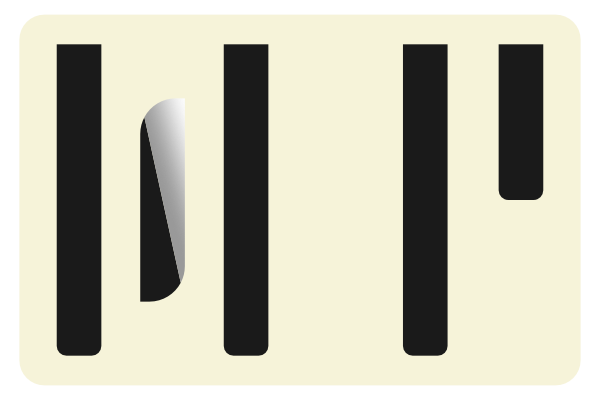

Piano wire tends to be very springy and hard to control. New piano wire comes in long lengths that are wrapped into tight coils. Piano wire manufacturers package these coils in a few different ways: canisters, sheet metal brackets, zip ties, and wire brakes. Each method has its advantages and disadvantages. I definitely prefer to use wire brakes, as they offer the most secure hold on the wire as well as the most control when unwinding a length of wire.

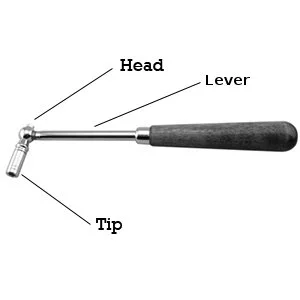

When these wire brakes come in from Schaff, the center bolt is usually overtightened to keep the wire from potentially unwinding during shipping. The first thing I do is loosen the bolt a little bit until the arm can rotate around the coil with some friction. This is done by holding the thumbscrew with one hand and turning the wing-nut on the other side just a bit with the other hand. Sometimes the wing-nut is so tight that a pliers is needed to turn it.

When working with piano wire, I wear some thin cotton gloves to keep the oils from my fingers off of the wire. These oils will cause the bare steel wire to rust very quickly.

To use the wire brake, hold the arm of the brake in between the thumb and index finger of one hand. Make sure you are not hanging on to the round part of the brake. Grab the end of the wire with a pliers and pull a length of wire out of the brake. The round part of the brake will spin as the wire unwinds.

Once I have pulled as much wire as I need, I use the pliers to squeeze the wire against the bend at the tip of the arm. This causes a tight bend in the wire that will catch in the small hole in the arm and keep the wire from unwinding.

The wire brake can now be put away until the next time it is needed.

I have been servicing and tuning pianos in NOLA since 2012 after first becoming interested in piano technology in 2009. With a background in teaching bicycle mechanics, I bring a methodical mindset and a love of sharing knowledge and skills to the rich musical culture of New Orleans.